First steps

In this section, we will initialize our first Git repository, learn to explore it, and create a few commits.

Get a mock project

Let’s download a mock project with a couple of files to practice with.

1. Download the zip file

Navigate to a suitable location (e.g. cd ~), then download the file with:

curl --output project.zip https://mint.westdri.ca/git/project.zip2. Unzip the file

Unzip the file with:

unzip project.zipYou should now have a project directory with a number of subdirectories and files. This is the project we will use today.

3. Enter in the project root

cd in the root of the project:

cd projectInspect the project

First, let’s have a look at our (very small) mock project.

Let’s list the content of project:

ls -Fdata/

ms/

results/

src/There are 4 subdirectories.

ls -a # Show hidden files.

..

data

ms

results

srcAs you can see, there are no hidden files.

ls -R.:

data

ms

results

src

./data:

dataset.csv

./ms:

proposal.md

./results:

./src:

script.pyNow we can see the content of each subdirectory.

You probably don’t have the tree command on your machine, so this won’t work for you, but don’t worry about it: this is only to show you the same result in a more readable format:

tree.

├── data

│ └── dataset.csv

├── ms

│ └── proposal.md

├── results

└── src

└── script.py

5 directories, 3 filesLet’s look at the content of the files.

This is our very exciting data set:

cat data/dataset.csvvar1,var2,var3,

1,2,1,

0,1,0,

3,3,3And a no less exciting manuscript (the proposal for our project):

cat ms/proposal.md# Summary

This is the summary for our proposal.

# Funding

Information on funding for the project.

# Methods

Here we have some methods using our Python scripts.

# Expected results

We hope to achieve a lot.

# Conclusion

This is truly a great proposal.And finally, a Python script:

cat src/script.pyimport pandas as pd

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

df = pd.read_csv('../data/dataset.csv')

df.plot()

plt.savefig('../results/plot.png', dpi=300)Initializing a Git repository

Our project is just a bunch of files and subdirectories. To turn it into a Git repository, we run:

git initInitialized empty Git repository in project/.git/Make sure to be at the root of the project (here, inside the project directory) before initializing the repository.

Git is verbose: you will often get useful feed-back after running commands. Read them!

When you run this command, Git creates a .git repository. This is where it will store all its files (all those blob objects, pointers, and other files).

You can see that this repository was created by running:

ls -a.

..

.git

data

ms

results

srcIf you run git init in the wrong location, you can easily fix this by deleting the .git directory that you created (e.g. rm -r .git).

Git commands

As you might have already noticed, Git commands start with git.

A typical command is of the form:

git <command> [flags] [arguments]Example of a command we used to configure Git:

git config --global "Your Name"Example of a much simpler command with no flag nor argument:

git initStatus of the repository

One command you will run often when working with Git is git status. It gives you information on new changes to your project:

git statusOn branch main

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

ms/

src/

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)There is a lot of information here:

- We are on branch

main. That is the default name for the branch that gets created automatically as soon as we initialize a Git repository. - There are no commits yet (normal: we just initialized a new repository).

- There are untracked files in our repo.

It is time to create a first commit…

Creating commits

Remember that commits are those “snapshots” of your project at certain moments in time. You should create a new commit whenever you think that your project is at a point to which you might want to go back to later. There is no rule about when or how often to create commits: it is really up to you.

Before we create our first commit, we need to decide what file(s) we want to add to this commit.

We could add everything.

We can also be more selective and add files one by one.

We can even add only sections of files.

How do we tell Git what to add to the next commit?

The staging area

Git has a staging area: a way to select what to add to the next commit. Files (or sections of files) get added to the staging area with git add.

To add all the files at once, we run, from the root of the project:

git add .The . represents the current directory. Because Git adds files recursively, this will add all new files.

To add a particular file, we add its path as an argument to git add.

Example:

git add ms/proposal.mdTo add all the files in a directory, we add the path of that directory as an argument to git add.

Example:

git add msSince there is a single file in the ms directory, both commands will in our case lead to the same result.

Let’s run that last command:

git add msIt looks like nothing happened. Did it work? How can I know?

Answer: by running git status again. That’s the command to go to whenever you need to get some update on the status of the repo:

git statusOn branch main

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: ms/proposal.md

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

src/It worked! We can see that the content of the ms subdirectory is ready to be committed. It is in the staging area.

Your turn:

What if we change our mind as to the composition of our first commit and we want to create our first commit with the Python script instead? To do that, we need to unstage proposal.md first.

How can we do that? Give it a try.

Then, how can we stage the Python script?

Committing

Once we are happy with the content of the future commit, it is time to create it. The command for this is git commit.

Remember that each commit contains the following metadata:

- author,

- date and time,

- the hash of parent commit(s),

- a message.

The first three can be set by Git automatically (you have configured Git so it knows who the author is).

Git has no way to come up with the forth one however. You need to create it yourself.

If you run git commit, Git will open your text editor so that you can type the message. If you want to enter the message directly from the command line, you use the -m flag followed by the quoted message:

git commit -m "Initial commit"[main (root-commit) 61abf96] Initial commit

1 file changed, 19 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 ms/proposal.mdWe now have a first commit. Its hash starts (in my case—yours will be different of course) with 61abf96.

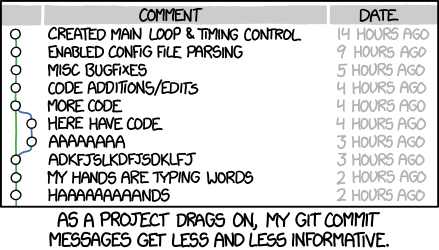

Good commit messages

It is suggested to:

- use the present tense,

- the first line is a summary of the commit and is less than 50 characters long,

- leave a blank line below,

- then add the body of your commit message with more details.

Example of a good commit message:

git commit -m "Reduce boundary conditions by a factor of 0.3

Update boundaries

Rerun model and update table

Rephrase method section in ms"Future you will thank you! (And so will your collaborators).

If we run git status once more, we now get:

On branch main

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

data/

src/

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)The directory ms has disappeared from the list of untracked files: its content has now been committed to history.

Understanding the staging area

New Git users are often confused about the two-step commit process (first, you stage with git add, then you commit with git commit). This intermediate step seems, at first, totally unnecessary. In fact, it is very useful: without it, commits would always include all new changes made to a project and they would thus be very messy. The staging area allows to prepare (“stage”) the next commit. This way, you only commit what you want when you want.

Let’s go over a simple example:

We don’t always work linearly. Maybe you are working on a section of your manuscript when you realize by chance that there is a mistake in your script. You fix that mistake. On your next commit, it might make little sense to commit together that fix and your manuscript changes since they are not related. If your commits are random bag of changes, it will be very hard for future you to navigate your project history.

It is a lot better to only stage your script fix, commit it, then only stage your manuscript update, and commit this in a different commit.

The staging area allows you to pick and chose the changes from one or various files that constitute some coherent change to the project and that make sense to commit together.